The Whiting Cemetery

Anthony Borgo February 2020

George Roberts

George Roberts bought the first tract of land that would become the Whiting-Robertsdale area on March 6, 1847. At this time the area wasn’t much more than a swampland, perfect for hunters. It wasn’t until the arrival of the railroad in 1874, that the Whiting area began to truly become a settlement. With the railroads came the men employed in their construction and maintenance; with the men came their families.

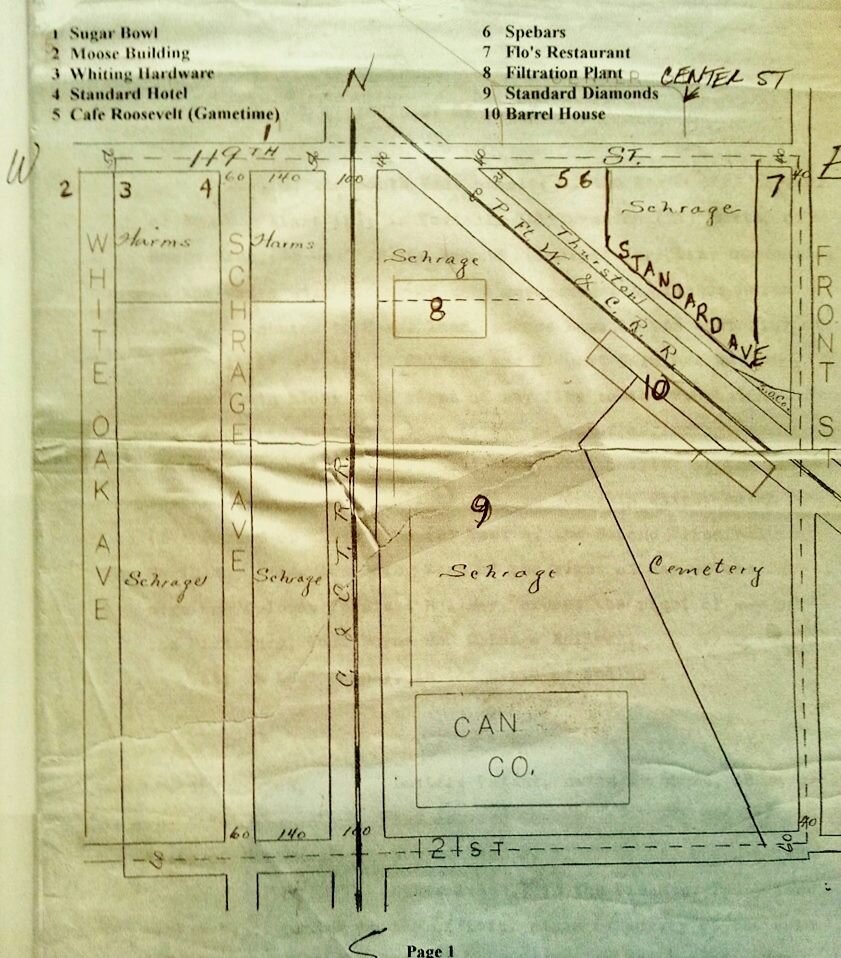

Life was tough for Whiting’s early pioneer families. Many children perished early in their lives. The life expectancy in the 1880s ranged between 39 to 47 years. According to Schrage's Forth Addition, Abstract of Title a Warranty Deed dated Sept. 15, 1863 property was acquired in the form of four acres to establish a cemetery on a sand ridge for the sum of $28.00. A Quit Claim Deed was issued Jan. 3, 1882 for the same parcel of land platted as the Whiting Cemetery. The cemetery was located within the “Oklahoma” section of Whiting.

Henry Schrage

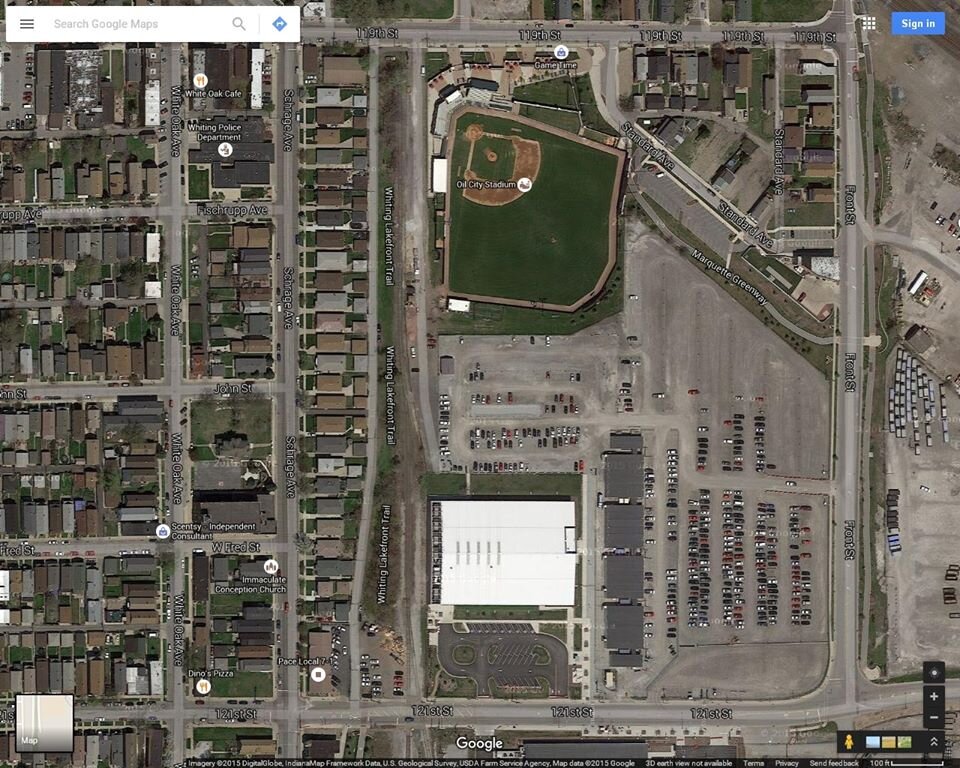

Henry Schrage realized the need of a cemetery in the Whiting vicinity and allowed the construction to commence on land that he owned. The legal description read as follows: “being the part of the southwest quarter of the northwest quarter of section eight, township thirty-seven, range nine, west of the second PM.” Geographically, the property was located fifty links to the right of way of the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago railroad Company. Today, the property would be located just east of the BP Burton Center on 121st Street. British Petroleum now uses the spot as a parking lot.

According to the “Historical Edition” of the Whiting Times, citizens of Whiting celebrated Memorial Day or Decoration Day as it was called then with a grand parade. Mrs. William Brown recalled, “Memorial Day was the big day for the school children. The day before we would gather flowers and make wreaths and keep them in tubs of water until the next day. Then all the Civil War veterans and the school children would parade from the Old Whiting High School to the little cemetery which stood where the Standard Oil barrel house is now and place flowers on the graves of soldiers.”

However, over time the practice and the cemetery began to fall out of favor. According to the May 29, 1908 Hammond Times, “There will be no special service in honor of decoration day. The majority of the people will wend their way to Hammond, as has been the custom for the past few years since the Whiting cemetery has been deserted. The soldiers of the Spanish-American war and also the members of the G.A.R. will participate in the parade in Hammond.”

Since 1903 the graves at the Whiting cemetery had started to be neglected. As a result, the city’s leaders decided it was time to make some changes. According to a December 7, 1912 Hammond Times editorial titled “The Passing of the Cemetery”, posterity will praise the actions of Mayor Beaumont Parks and Aldermen Paskovitz and Burton.

Beaumont Parks

“Time was when the dead were buried in the church yard in the heart of the cities and villages of this country. Then they were forced into the suburbs and now the laws of the state of Indiana prohibit the laying out of a cemetery within the corporate limits of any city.” In addition, Whiting’s city leaders acknowledged that the ground was too valuable to remain as a cemetery. It was the plan of Mayor Parks to use the property for manufacturing purposes.

The editor of the Times goes on, “Besides cemeteries obstruct progress. They are unsanitary. They intrude themselves on certain districts, they prevent the opening of streets, their owners seldom try to hide their unsightliness from the public and in short they have no place in a progressive community.”

The Standard Oil Company had their eye on the Whiting cemetery for years. According to a March 19, 1903 article in the Fort Wayne Sentinel, “Standard Wants Cemetery.” Standard Oil had recently purchased the “Oklahoma” section of Whiting which housed approximately 800 people at this time. “The company is also trying to purchase the Whiting cemetery, which though unused at present, contains hundreds of graves. The ground is owned by Henry Schrage, a county official, and the company is trying to force him to sell the acreage, so that it may build new refineries over the forgotten graves marked by blackened tombstones.”

On December 2, 1912 the city of Whiting passed Ordinance 215: An Ordinance For the Vacating of Whiting Cemetery. According to the Ordinance the remains of all people interred must be exhumed and relocated to another cemetery. Any unclaimed bodies were to be removed and properly reinterred to another cemetery at the city of Whiting’s expense. Following the ordinance was a list of the names of all deceased persons whose bodies remain interred at the Whiting cemetery.

According to a February 8, 1913 Hammond Times article, Standard Oil was able to retrieve the title to the Old Whiting Cemetery. “Record of a deed made at Crown Point shows that the Standard Oil company has paid $5,000 for four acres of Whiting property sold by Henry Schrage. If you adjust for inflation $5,000 today would be approximately $130,000.

On March 17, 1913 work to exhume and remove the bodies from Whiting’s graveyard began. Whiting’s city council accepted the bid of Undertaker C.A. Hellwig for the removal of the bodies from the Whiting cemetery to a cemetery located across from the Greenwood cemetery in Hammond. Undertaker Hellwig’s bid was $16 for the removal of each body and $2 for each headstone or monument that needed to be relocated.

According to Henry Schrage’s records there were only supposed to be approximately seven hundred internments. However, when the bodies started to be dug up, the number was closer to eleven hundred. A great many burials had taken place prior to 1882, when the cemetery was platted. The March 19, 1913 edition of the Whiting Call stated that these unofficial graves were laid with no regards to the points of a compass, “having been placed at right angles to the ridge of sand which formed the nearest thing to a hill that existed here in those days.”

Concordia Cemetery

Interestingly, Hellwig discovered that there were some bodies that were found in a remarkable state of preservation. One body, for instance, was found wearing heavy leather boots, and another was discovered with several dollars of currency in a pocket of his clothing. In addition, Hellwig stated that some of the bodies weren’t even found in caskets. Sadly, main caskets contained multiple bodies of young children, sometimes up to five bodies were discovered. In one casket only a human leg was found, which was believed to belong to Stevenson’s son.

Oak Hill Cemetery

The Whiting City Council also hired James Freeman. He was appointed to act as a representative of the city and to keep records of the bodies that were found. The records were transcribed in a special book that was kept at the city clerk’s office. Today, a copy of Freeman’s records can be viewed in the Local History Room of the Whiting Public Library.

The bodies were relocated to the city graveyard which Whiting had purchased, it was located on Hessville Road, near the St. John’s Cemetery. According to James Freeman’s records bodies were relocated to the Oak Hill Cemetery, Concordia Cemetery, the Greenwood Cemetery, the Greek Catholic Cemetery, and the St. John Cemetery.

St. Nicholas Cemetery

The city of Whiting furnished a new burial plot at this location, where the bodies were re-interred. Any family members of the deceased who were not satisfied with this arrangement was given an alternative. The city was willing to have their loved ones reinterred in any cemetery of their choosing. However, city officials would only pay up to $21 of the cost of the burial, anything over that price would be the responsibility of the family member.