U.S. Troops Storm 119th Street

Jerry Banik

August, 2025

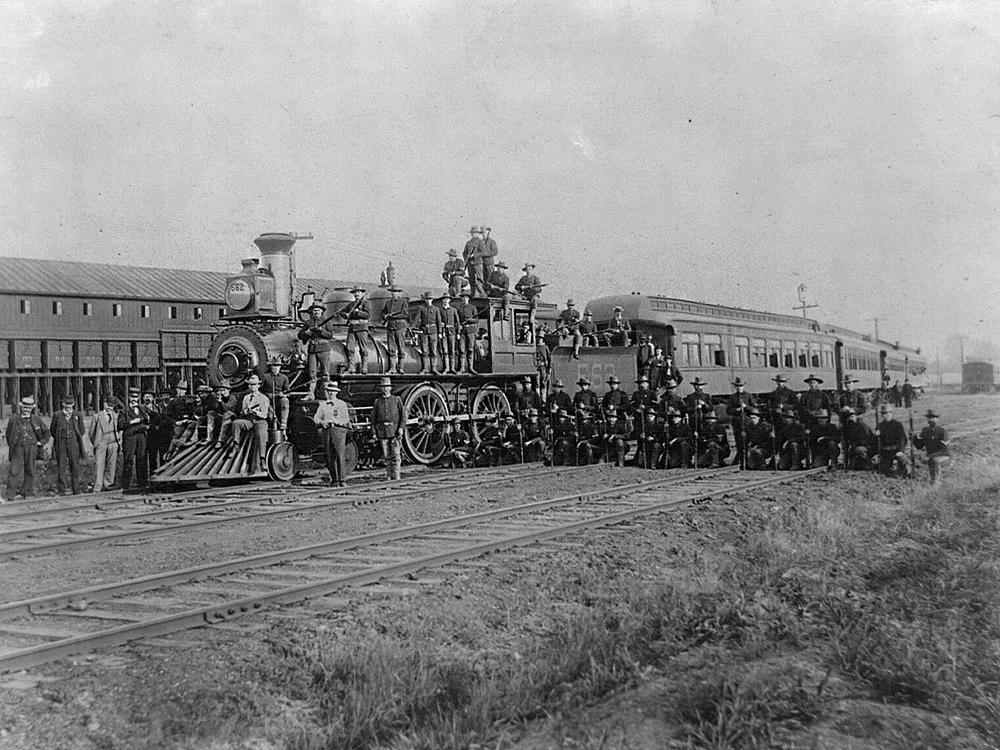

Early one warm, Whiting, July evening, as the streets were filling with refinery and factory workers returning from their day shifts, a train pulled to a stop on the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern railroad tracks, next to the small station at the north end of Front Street. Suddenly, scores of federal troops and U.S. special marshals poured from the railroad cars. With guns drawn they rushed up Front Street and down 119th as far as Ohio Avenue, shouting and forcing people to clear the streets, detaining and arresting anyone who dared not comply. The soldiers were soon joined by a company of state militia from Hammond.

What on earth was going on?

The best of times?

In some ways, what Mark Twain called America’s “Gilded Age” was the best of times for Whiting and Robertsdale residents, but in 1894 they found themselves situated in the middle of some of the worst.

America had fallen into the worst economic depression in its history the previous year. The city of Whiting had not yet even been incorporated, as businesses closed and banks failed all across the country. There was a dangerous run on gold from the U.S. Treasury. The stock market plummeted. Unemployment in many states rose above 25%. Shantytowns of impoverished Americans sprung up on Chicago’s Lake Michigan shores during this “Panic of 1893.”

Those hard times eventually led to an ugly railroad strike that began in May, 1894.

A wildcat strike lights the fuse

Source: Pullman National Historical Park, U.S.National Park Service

On South Chicago prairie land, adjacent to Lake Calumet, was the Pullman Palace Car Company that manufactured railroad passenger cars.

There, many Pullman workers lived in the company town that George Pullman built and owned.

But after he laid off hundreds of workers, drastically cut wages and refused to lower their rents or the prices in his company stores, Pullman’s non-union workforce walked off their jobs in a wildcat strike.

Within a month after the walkout, the American Railway Union (ARU), led by Eugene Debs, launched a sympathetic national boycott of all American railroad companies that pulled Pullman cars.

The boycott effectively halted much of the nation’s railroad traffic.

On June 29, a riotous crowd attending one of Debs’ union rallies in Blue Island, Illinois set nearby buildings on fire and derailed a locomotive from a train that was carrying U.S. mail. This triggered the federal government to issue an injunction against the strikers on July 2.

Within days, President Grover Cleveland found it necessary to dispatch troops to the region as the violence of strikers and their sympathizers escalated.

On June 30, strike sympathizers destroyed several cars on the Illinois Central tracks by south Chicago’s infamous Grand Crossing railroad intersection.

1907 Chicago Tribune photo

A side note: It was at Grand Crossing, some forty years earlier, that an express train had broadsided a passenger train that crossed the tracks in front of it, killing some twenty people.

On that express train was a conductor by the name of Herbert “Pop” Whiting, whose last name would be chosen to christen the newly incorporated town of Whiting, Indiana four decades later.

Whiting gets involved as things get ugly

Twenty two railroads had operations in Chicago and most of them ran their trains through Whiting, Robertsdale and Hammond, where many railroad men worked in switching yards, shops, depots and stations. The general managers of those railroads united to oppose the American Railway Union’s boycott on Pullman cars.

Whiting’s newspaper, The Democrat, reported that on July 7, a “moderate sized audience” gathered at Goebel’s Opera House on John Street in Whiting to listen to speeches from American Railway Union organizers. By the meeting’s end, nineteen men had signed on, and Whiting had a new ARU lodge.

According to claims, ARU president Debs threatened that, "the first shot fired by the regular soldiers at the mobs in Chicago would be the signal for civil war."

As violence spread to city after city, and railyard after railyard, U.S. Senator Cushman Davis warned that Debs and his associates "are rapidly approaching the overt act of levying war upon the United States."

From the Centralia, Illinois Sentinel, July 9:

“The seat of war in the railroad strike was transferred to-day to Hammond, Ind., just across the border line, where, from an early hour, mob violence reigned supreme. Two companies of regulars were dispatched to the scene. Late this afternoon there was a pitched battle between the regulars and the mob. This is the list of casualties:

Charles Fleisher, carpenter, married, aged 35, a resident of Hammond, was killed instantly, a bullet entering his abdomen and passing through the body.

W. H. Campbell, shot in right thigh, probably fatal.

Victor Setter, shot in knee; amputation of leg necessary; condition critical.

Miss Annie Flemming of East Chicago, bullet wound in right knee; not serious.

Unknown man shot in right leg; amputation probably necessary.”

Details of our local riots and destruction were on the front pages of newspapers all across the country. Below, for example, are just some of the clips from California newspapers (each can be enlarge by clicking on it). These incidents and others all took place within a dozen miles of Whiting and Robertsdale, as the crow flies:

State and federal troops arrive in Whiting

The Whiting Democrat, which was sympathetic to the working man, ran this headline above one of their strike articles.

Downstate, where support for the strikers was not nearly as strong as it was locally, the Indianapolis Journal reported that rumors abounded of a “riotous spirit” that had broken out in Whiting, and that a mob was ruling the town. Two U.S. Marshall’s were said to have been run out of town for interfering with a mob that was trying to stop a train on the Fort Wayne Railroad. “Word was received by General Robbins that three companies of U.S. troops had reached there to assist the militia in suppressing the rioting.”

On July 12, The Democrat wrote the following about federal troops and state militiamen arriving in Whiting:

Image source: Whiting Democrat, July 12, 1894

About five o’clock last night just as the hundreds of workmen were returning from their work and were filling the streets with men, a special train pulled in on the Lake Shore road and from it rushed a company of federal troops and about a dozen special U.S. marshals. [The Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway was one of the railroads whose tracks ran through town along modern day Whiting Park. They had a station on their tracks at what today is the Front Street crossing.] The troops at once drew up in line beside the trains while the deputies rushed up 119th street, shouting to the people to clear the streets upon danger of their lives. On they went, past the post office and DEMOCRAT office to the Ft. Wayne tracks driving everyone before them. Here and there an inquisitive citizen stopped to look back to see what was the trouble, when he would be seized and brutally kicked or beaten and driven on by a Winchester or revolver. By the time they reached the Ft. Wayne track fully twenty-five had been beaten or kicked by the deputies, and between ten and fifteen put under arrest.

The Democrat story continued: The deputies rushed through the streets as fast as their drunken legs could carry them, and the regulars went on double quick. It transpired that there had been an attempt made by some strikers to wreck a scab brakeman on the Lake Shore dummy [“Dummy” was a term for locomotives used for slow-speed switching, and sometimes for the railroad sidings; “scab,” of course, was a worker who crossed a picket line during a strike], and they had threatened to destroy the depot force and the beautiful new depot buildings and all the lives it contains. By the time the deputies had worn themselves uselessly out, a company of state militia from Hammond put in their appearance to assist in quelling the riot, and the regulars and most of the deputies returned to the city to the delight of the people. It is enough to cover the cheeks of an American citizen with the blush of shame that such an indecent and unjustifiable drunken attack should have been made upon a quiet and orderly community.

In the end…

Some businesses found it necessary to re-assure their customers that they still had commodities to sell. This ad appeared in the July 19, 1894 issue of The Whiting Democrat.

Every day necessities had become harder and harder to come by.

The presence of troops, the losses of life and tens of millions of dollars in property damage at the hands of the rioters soon became more than the public would bear. People feared the potential for anarchy. They had grown tired of the disorder, the disrupted trade, the lack of normal passenger and mail service.

By August the strike was over. But by then not even famous attorney Clarence Darrow, who defended Eugene Debs against federal charges brought against him, could save Debs and other leaders of the ARU from prison sentences, and the union was dissolved.

One more thing

A sad, related event of that tumultuous July was the fiery destruction of many of the structures still standing from the Columbian Exposition, Chicago’s magnificent World’s Fair in Jackson Park, less than a year earlier. As the railroad strike raged on, the smoke and flames from the once beautiful “White City” could be viewed from the less grandiose “Oil City” of Whiting, across the curve in the lake shore.

The Whiting Democrat described the spectacle:

Last Thursday evening there occurred the most destructive of all the many fires of the World’s Fair buildings, and the great crowds of a year ago were emulated by the large number of people who gathered to view the brilliant spectacle. There could be seen across the lake a large black cloud of dense smoke arising. Great crowds boarded the street cars and started to visit the fire. The flames spread with startling rapidity, first to the Administration building, thence to the Mining, Electricity and Manufactures buildings. The flames devoured the beautiful and unprotected buildings. Wind blew the flames across to Machinery Hall and the Agricultural buildings. The fire burned itself out in time for the people of Whiting to take the street cars and get back home before the cars had quit running. A large number of people from Whiting were at the park viewing the fire and felt amply repaid for their trouble by the beauty of the scene.

The sad result of the World’s Fair’s July fire. In the upper left of this photo can be seen the Fair’s iconic Statue of the Republic, its right hand still holding aloft a globe with an eagle perched atop it. Because the statue was on a pedestal in the water of the fair’s Great Basin, it escaped the fames, only to be destroyed later on orders of Jackson Park’s commissioners. Image source: Chicagology.com