The Tied House System That Left Its Mark on Whiting

Ron Tabaczynski

November 2025

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Whiting was a booming industrial town shaped by an influx of workers, growing traffic on its railways and an expanding refinery. Like any industrial town of the time, one of the fixtures of the community was the neighborhood saloon. But in the day, the saloon was more than a place to drink. It was a social hub for workers and a community meeting spot for those residing in boarding houses and sparse living spaces. For immigrants far from home, it was also a little bit of the old country in their new city. Just as Whiting churches were built around ethnicity, the saloons were also often ethnic-centric establishments.

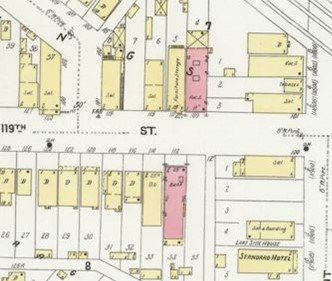

“Sal” for “saloon” was a common notation on Sanborn Fire Insurance maps showing building uses in early 1900s Whiting.

The Derby was operated by Otto Bauer in the early 1900s. It was a Pabst Brewery tied house located at the present intersection Schrage and Indianapolis Boulevard.

Although saloons were common across American cities, Whiting’s concentration was remarkable. Within the city’s compact footprint, as many as fifty saloons operated at once. Many were concentrated in the area known as “Oklahoma” before it became part of the Standard Oil refinery. Front Street and 119th Street, were also home to many saloons, but virtually every residential block had at least one, and perhaps several saloons. Many were on the corners, but others were in the middle of the block, and often next to another saloon. Others were located in boarding houses, hotels or opera houses and dance halls.

Many of these saloons operated as tied houses, establishments owned or controlled by a specific brewery. The tied house model originated in nineteenth century England, but American breweries were quick to replicate it as a way to deal with intense competition and increasing government restrictions. Having a direct channel to sell their beer allowed the breweries to be involved in beer production, as well as its wholesale distribution and retail sale.

A tied house was, at its core, a business arrangement. Today it would be known as “vertical integration.” Under the tied house model, breweries paid for licenses, extended loans, leased buildings, provided bar fixtures, or covered start-up costs for a saloonkeeper. Many also constructed the buildings, often adorning them with brewery insignias molded into brickwork, branded backbars, or stained-glass transoms with stylized logos. In return, the saloon agreed to sell only that brewery’s products – with simple but very restrictive written agreements.

Although this example is from Chicago, it is typical of the exclusive agreement that a Whiting saloon-operator would have used with brewery in the early 1900s.

Whiting was fertile ground for tied houses. Its dense working-class neighborhoods provided a strong customer base. The proximity to Chicago and Milwaukee, two of the nation’s brewing giants, also made Whiting a natural extension of their competitive market strategies. Brewers like Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, and Miller—along with major Chicago firms like Conrad Seipp Brewing, Schoenhofen-Edelweiss Brewery and the Manhattan Brewing Company—established strong footholds in the Calumet Region by financing saloons where their beer would be sold exclusively.

Before long, Whiting’s main streets and side avenues featured a patchwork of saloons tied to different breweries, each vying for visibility and customer loyalty.

Long before it became an iconic restaurant, Phil Smidt’s was known simply as “Phil’s Place,” one of many fish houses near Wolf Lake. Under a tied house agreement, customers dining on fish or chicken dinners could also order a Utah Brau made by the Standard Brewery in Chicago. Later, Phil would find himself in court being sued by the brewery for allegedly selling a competitor’s beer.

Inside a typical tied house, the experience was familiar and predictable. A long barroom dominated the front, with the backbar lined with brewery-branded mirrors and hardware. Workers could find a free lunch of sandwiches, soups, or pickled items—an incentive that encouraged return visits and larger beer sales.

But tied houses also carried problems that reformers quickly seized upon. Because breweries depended on high-volume sales from their contracted saloons, they often pressured saloonkeepers to push more beer. Extended hours, aggressive promotions, and the density of saloons in certain neighborhoods made the tied house system a lightning rod for reformers.

The relationship between tied house operators and their sponsoring breweries was not always a pleasant one. Agents for competing breweries would sometimes “negotiate” new deals as an enticement for a saloon keeper to shift his loyalty.

During the days of the tied house, and even in the early years of alcohol prohibition, breweries frequently took their former partners to court for breach of contract or to foreclose on debts.

Many workers and immigrants lived in boarding houses that lacked private kitchens or communal spaces. Compared to lonely, sparsely furnished rooms, saloons became welcome alternatives to enjoy the little leisure time that workers had. This saloon was in the boarding house operated by Fred and Ida Vogel at Indianapolis and Roberts Avenue. circa 1915

Temperance advocates argued that brewery subsidies encouraged excessive drinking and made saloonkeepers financially beholden to companies whose only goal was promoting sales. As Indiana adopted statewide prohibition in 1918 and national prohibition followed in 1920, the era of the tied house came to an abrupt end. When the United States emerged from Prohibition, regulations largely put an end to the tied house system by implementing a three-tier system where production, distribution and retail sale of alcohol are kept separate.

The images at the top left shows the John Urban saloon, a tied house and buffet in 1915. Below that is the building as it looked in 2025. The image at the right is of John’s Pizza (formerly Just Dotty’s. Although it housed various businesses until it was torn down in 2017, it was the building shown at the top of this article which was built in 1898 and operated as the Derby by Otto Bauer as a Pabst Brewery tied house in the early 1900s. A walk around present-day Whiting and Robertsdale reveals many former commercial buildings that likely had some history as saloons with many probably have been tied houses at some time.

Today, several former tied house buildings still stand in Whiting, quietly marking the places where generations of refinery workers and immigrant families once gathered. They remain important touchstones in understanding Whiting’s early life and serve as reminders of a time when beer shaped the city’s social culture as well as its streetscape.