Artist’s conception of summers at Wolf Lake Beach, circa 1967.

The Golden Age of AM Music Radio Transistor radios, summers at Wolf Lake Beach…and WMMO?

Jerry Banik July, 2021

In the 1950s, Bell Laboratories developed the modern transistor, a technological advance that spawned the growth of miniature radios that were no longer tethered to electric wall outlets. At the same time, millions of Baby Boomers were coming of age and putting their stamp on a new style of music. The convergence of those two phenomena resulted in a big change in American popular culture, and that change was possibly nowhere more evident than on Wolf Lake Beach in the summers of the 1960s and ‘70s.

In that era, Neal Price’s and Orr’s TV on 119th Street, and Star Sales on Calumet Avenue were popular spots to buy your first “pocket” radio, or a larger portable if you had the cash. Wide and thick, and rivaling house bricks in weight, the first pocket models were really only “pocket” if you had pockets the size of Captain Kangaroo’s, but soon they got sleeker and lighter.

Your transistor radio was usually just referred to as your transistor. You took it everywhere you thought it would not be lost, stolen or ruined. Wolf Lake Beach was the exception to the lost, stolen or ruined rule. There your radio was subject to all three of those possibilities, but to go to the beach without it would be like a guy sporting a flattop without Butch Wax. You just didn’t do it.

If you’re struggling with that reference, your dad can probably help you.

By adding a tubular extension speaker, suddenly the tinny music coming from your little transistor sounded like you were sitting in Carnegie Hall—that is, if all the musicians were playing kazoos and the singers sang through cardboard tubes from paper towel rolls.

One of the cooler things to happen during the heyday of AM music radio had more to do with industrial design than with music, news and weather. It came as the result of competition among the many radio manufacturers of the day.

The surest way for companies to sell more radios was not by improving sound quality, battery life or reception, but by creating hip, new space age designs and colors. Bakelite material enabled almost endless possibilities. Most had the same, thin, tinny sound, but they all looked like they came from different planets.

The transistor radio helped make the ‘60s and ‘70s the Golden Age of AM Music Radio. The FM radio band was unhip, fit only for old people and classical music snobs. AM radio was “where it was at”, and WLS was the king of AM, especially at Wolf Lake.

WLS had been around since 1924, having been founded by Sears, Roebuck & Company, whose slogan, “World’s Largest Store” provided the station’s call letters. The Big 89, The Rock Of Chicago, The 50,000-Watt Tower of Power, ruled at Wolf Lake Beach, which was a beach in the same, generous sense that the first pocket radios were pocket-size.

WLS claims to have been the first U.S. station to play a record by The Beatles by playing Please Please Me on Dick Biondi's show in February, 1963. In doing so the station got a jump on another 50,000-watt Chicago station, WCFL. Located at 1000 on your radio dial, WCFL later pursued the same, age 18-34, audience. By the mid-1960s the two were in an all-out ratings war.

Just as, in the vernacular, WLS was simply “LS”, Big 10 WCFL was simply “CFL”. It was another old, Chicago station, and was owned by the Chicago Federation of Labor, hence their call letters. “The Voice Of Labor” adopted a Top 40 Rock ‘n’ Roll format in 1966 and quickly rose from 16th place in the ratings to as high as 2nd among the coveted 18-34 year-olds, but it took them until 1973 to briefly rise to #1.

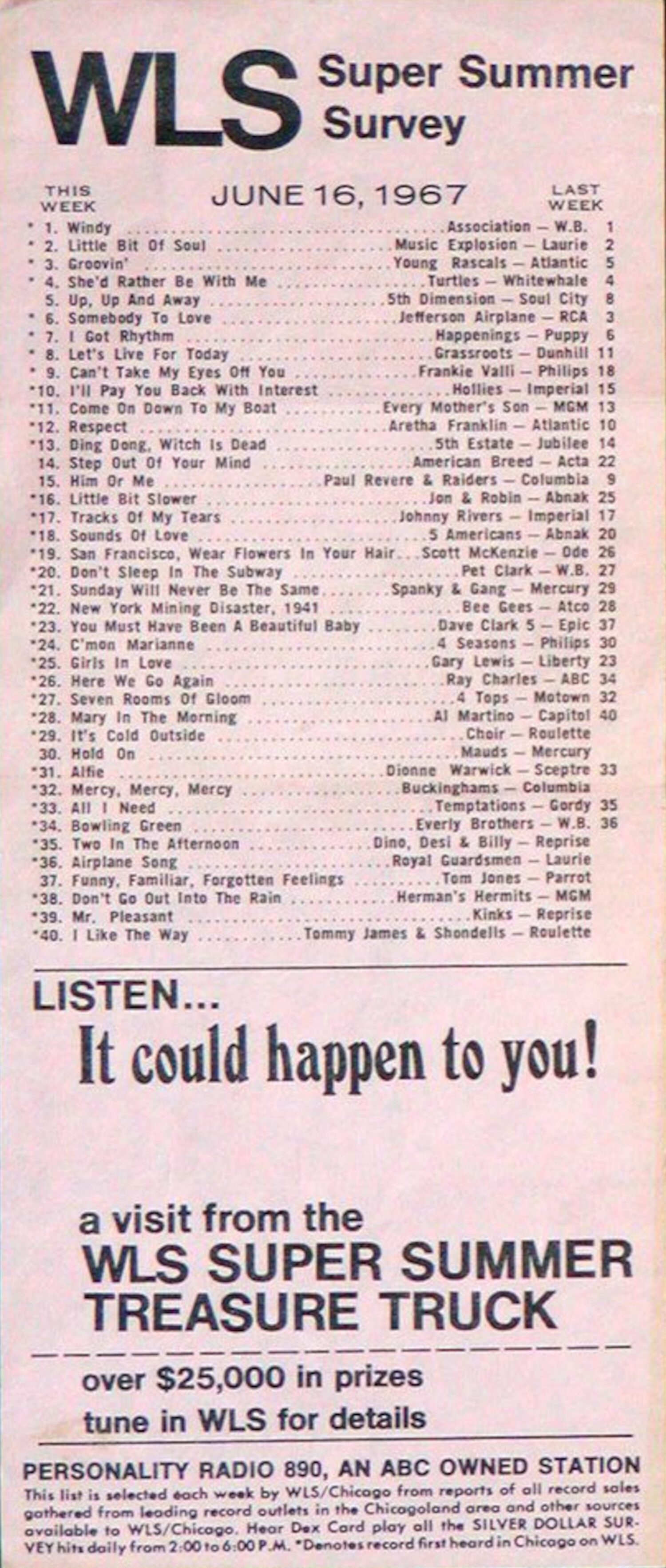

Meanwhile, in Whiting, Neal Price’s, in addition to transistor radios, sold “45s”, the popular, new record format, so named because the one-song-per-side discs spun at 45 revolutions per minute. Price’s also featured listening booths where customers could try out newly released records before deciding whether or not to buy. Once a week, kids made a pilgrimage after school to Price’s to pick up the latest copy of the WLS Silver Dollar Survey. Later called the Super Summer Survey, and still later the WLS Hit Parade, it was the station’s list of the top forty hit records of the week. WCFL, not to be outdone, had its Solid Gold Survey, and later, the Sound Ten Survey.

Like counting the rings of a tree, today you can tell how old someone is by how many songs they know from these surveys:

Gene Taylor, Art Roberts, Dex Card, Chuck Buell, John Records Landecker and other disc jockeys introduced the music on WLS; Ron Britain, Barney Pip, Jerry G. Bishop and others did the same at WCFL. Stealing away each other’s on-air talent was common for both stations. Clark Weber, Joel Sebastian, Dick Biondi, Ron Riley, and Larry Lujack were among deejays who did stints at both WLS and WCFL.

On hot summer days, if you were able, you’d hit the beach at Wolf Lake, where you could show off your beach bod, or gaze at the swimsuited bods of the same kids of the opposite sex you saw fully dressed in school nine months of the year. Walking along you’d pass blanket after blanket where the sweet sounds of The Rock Of Chicago rose as you approached, then faded away as you passed, only to rise again at the next blanket.

Between songs, commercials hawked sun tan products like Coppertone (“Don’t be a paleface!”), Ban de Soleil (“For the St. Tropez tan!”), Sea & Ski (“Tan as dark as you can!”), and Tanfastic (“It’s not for your mother or your baby brother!”).

And then there was Tanya.

Just coconut oil and cocoa butter.

With no sunscreen, it fried plenty of unsuspecting sun worshipers.

Skin cancer in a bottle, tube or convenient spray can. Back then, who knew?

Eventually summer had to end, and for most of the beach crowd that meant back to school. But it didn’t mean your music radio fun had to end. Enter radio station WMMO.

Perhaps inspired by the European wave of pirate radio stations that transmitted from small ships moored at sea, out of reach of government enforcers, or perhaps just by the good, ol’ American spirit of adventure, a small group of radio enthusiasts from Clark High School created “radio station” WMMO.

WMMO stood for “Whiting’s Most Magnificent Organization”, or “With Music More Often”, depending on who you talked to.

It had a brief but memorable run. Because it was illegal as heck it could only be promoted by word of mouth, but the daring nature of its illegality made WMMO’s popularity spread through Clark like wildfire.

For a while it seemed Clark students talked about little else. Knowing whether or not the station was going be on the air on a given night, and where to find it on the dial, was an indication you were “with it”. If you didn’t know, you pretended to know. School was awash with rumors about who was running the station and from where, and that the Feds were hot on their tails. The fabricated stories would put today’s fake newsers to shame, and created a small army of fans all out of proportion to the little station’s actual reach.

WMMO, it was claimed, took song requests. Of course, the phone number at the house from which the station broadcast couldn’t be given out on the air (just as more than fifty years later this article won’t), but the number of a nearby telephone booth could. Reportedly, a WMMO runner would take requests at the phone booth, and run them back to the station house to be played. Oddly, most of the requests seemed to be for “Louie, Louie”.

Eventually, like all good things, the Golden Age of AM Music Radio had to come to an end. The writing was on the wall when the Federal Communications Commission approved technical standards that allowed FM stations to broadcast in stereo, something AM could not do. By 1970, FM stations were beginning to expand across America. Before the ‘70s ended, the top forty AM music format was fading away, and the top forty AM deejays, once the captains of the airwaves, began to slide into extinction.

That’s all the space we have for today, so…